On Practice

I consider understanding practice the most important thing I took from my education at Evergreen.

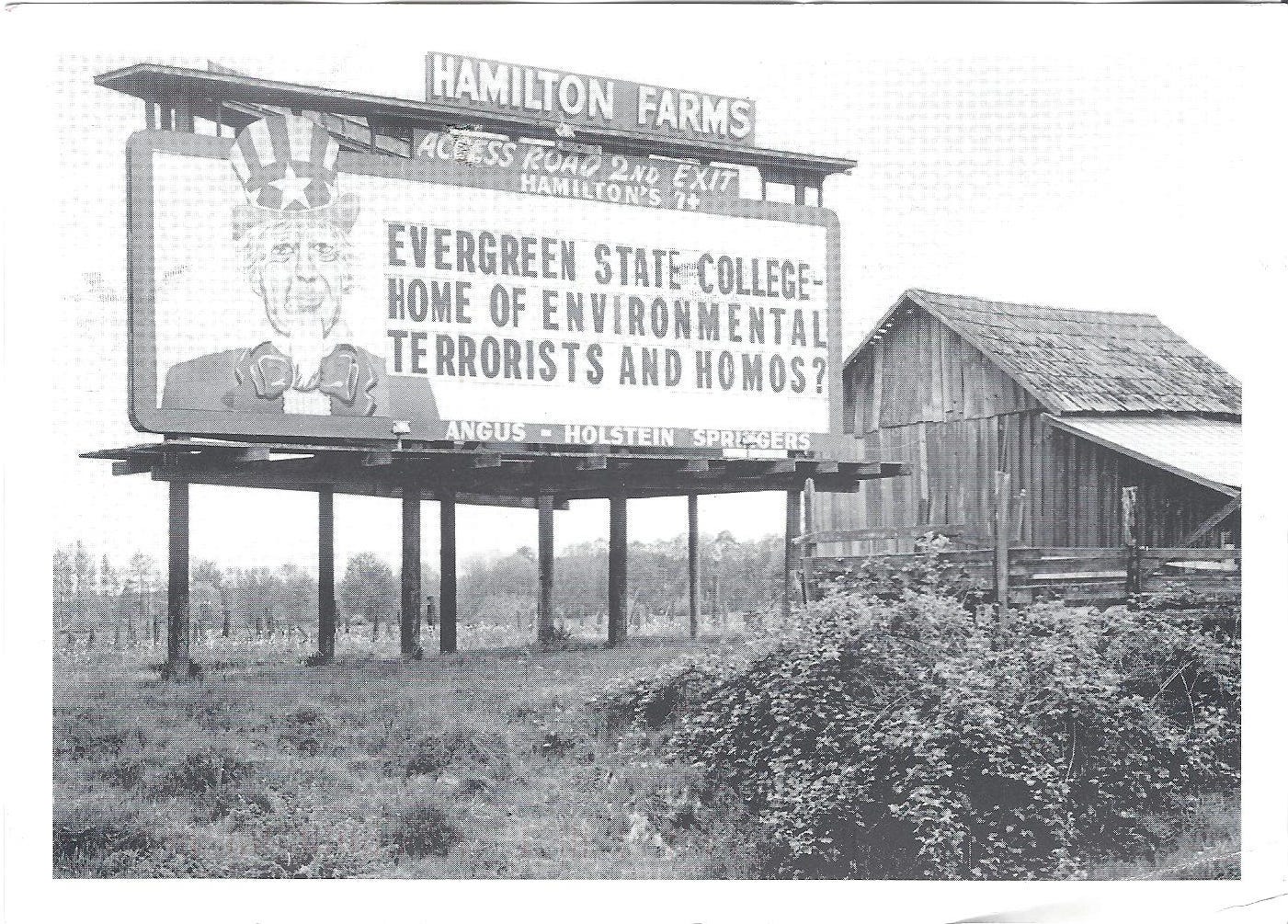

Like one of my fictional characters, when I graduated from high school, I only applied to one post-secondary institution: The Evergreen State College. I’d grown up outside of Olympia and I had always known about Evergreen, a liberal arts school with no majors, grades, or exams, known for its leftist politics and hippie atmosphere. “Don’t inhale in the dorms,” our high school chemistry teacher would joke. I’ve rewritten some of my ambivalence about my Evergreen education, because I believe in Evergreen’s original mission, and I’m endlessly interested in its history, and what others have gotten from their learning experiences there. My partner and fellow alum, Kaden Jelsing ‘06, for example, now holds a PhD in History.

I think I knew even then that I wasn’t ready to go to college, but my parents insisted that any gap would derail my education permanently. It’s hard to imagine what they might have thought of me then. I’d grown from an obsequious, people-pleasing child in gifted classes into a gay punk stoner who worked at McDonald’s. My best friend and I moved into an apartment together three weeks before our high school graduation. As I wrote in an unpublished piece of autofiction: We needed our own place to smoke pot and hook up with girls, which had proved difficult to do in our parents’ homes and tiresome to carry out my car.

If I wasn’t ready to go to college, I was absolutely not ready for the agency of building my own education, as Evergreen encourages with interdisciplinary programs and options for customized “contracts.” I began with a contract called “Marketing the Arts,” as an intern with Nomy Lamm. Then I moved into “Fiction/Nonfiction,” a creative writing class. Here, I met Amber, the only person besides Kaden I still want to impress. Once, paired to read sentences with rhythm and flow to one another, she read me Michelle Tea and I read her Tom Spanbauer. (Private to Amber: I fucking love you).

I momentarily struggle to remember the timeline. The next fall, I moved into the dorms and it didn’t work for me, so I dropped out winter quarter in order to get out of living in the dorms. That’s when I moved in with Kaden, as housemates. In the spring, I returned and took “Drawing a Life” with Marilyn Frasca, Lynda Barry’s teacher. This program opened up everything for me, everything: suddenly my life was enchanted. But I didn’t know what was going on – that I was healing and growing through expressive practice – and I didn’t know how to hold on to it. I was still working 40 hours a week at McDonald’s, but it was fully integrated into my artistic life, and the part of my life where I was falling in love with Kaden.

In the fall, Amber and I both enrolled in “Transcendent Practices,” an interdisciplinary program whose fields of study included yoga, ecstatic poetry, and meditative sculpture1. I had wanted to try yoga and meditation since I was a kid, and “ecstatic” was what I’d felt since I began practicing drawing and using Intensive Journal Workshop methods in Marilyn Frasca’s class. It seemed like a perfect fit.

It was not.

Many of the students in our fifty-person cohort had difficult, negative experiences. Amber and I have unpacked, framed, and reframed this repeatedly in the last twenty years.

“Transcendent moments favor the prepared,” read the course description. And while the first quarter was centered around the concept of “grounding,” none of the instructors seem to have considered the possibility supporting students during the crisis that so often comes concurrently with spiritual awakening. When the practitioner is so open and raw and walking around in the everyday world. I was, additionally, very out of touch with how to use my body, had not pushed on it since running the mile in PE class my freshman year of high school. As much as we could talk about approaching yoga without being goal oriented, I found myself thinking I hate myself when I couldn’t perform a pose. That was the same day Kaden asked me to marry him.

The immediate result of “Transcendent Practices” was an eight-month bout of depression, but in an underlying way, I remained angry and frightened by this experience for a long time. My mom even muttered about wanting to sue the school. But twenty years have passed, and I have learned so much about how to process, how to express, how to learn. Despite all the negative baggage from “Transcendent Practices,” I found ways to use what I learned about practice. I consider understanding practice the most important thing I took from my education at Evergreen.

Once (or more), we did an exercise examining why we would avoid our practices, what prevented us from practicing. I distinctly remember being aware of the need to make a space in my home in which to do the practice – needing to clean, first. I’ve always felt deeply uncomfortable about the famous quote by Dr. Clarissa Pinkola Estés, who says “I've seen women insist on cleaning everything in the house before they could sit down to write...and you know it's a funny thing about housecleaning...it never comes to an end. Perfect way to stop a woman.” I have known since I was twenty that I can’t practice in a messy house. It drags on me. I let myself feel slightly shamed by that Pinkola Estés quote for years (it helped to understand that I was nonbinary, not a woman), until I recognized that I could practice in whatever way worked best for me, even if I sometimes needed to take extra time to tidy my space before beginning.

We can tell our life stories so many different ways. There were other things going on that I could use to frame this time of my life. But I’m telling the story of my relationship with practice. It was five years before I tried yoga again. We lived in Bellingham, then, and I began taking lessons in Iyengar yoga. When I moved to Level II, I was watchfully aware when I became goal oriented and frustrated, and went back to Level I. It was about practice, not progression.

When we moved back to Olympia, I did various yoga classes around town for a year before I found Jessica’s classes. After another year of attending Jessica’s studio classes, she invited me to join the smaller group that practiced at her home. I always referred to this as “going to practice.” Kaden once told me he liked how I said that, as if we were a sports team. I remember turning down certain social invitations on Thursdays, and certain people being mad at me about it, telling me that I should skip my class. They didn’t understand my practice was a commitment to myself.

In EWU’s MFA2, our instructors told us that the two most important things we could take away from the program would be a community of writers, and the development of a writing practice. I had failed to keep my cohort together after “Drawing a Life,” despite taking down everyone’s names and email addresses, and I participated in three different writing groups when we lived in Vancouver that didn’t last (although they did their jobs in their times). I have no way of knowing who from my recently graduated fiction cohort will stay together or for how long, but right now we are meeting twice a month for check ins, mini workshops, and to set aside the time to write together. I could not have asked for a better cohort: I am grateful every day to have met these wonderful, smart, loving people. Any fears we had about the traditional nasty competitive atmosphere of an MFA program have been disproved.

As for my writing practice, I’ve pushed and pulled and forged ahead and lagged behind throughout the summer. The astrology and tarot have been all about structure, and shit is about to get real: I accepted a full-time job which starts next week. In a reassuring text message, Amber wrote to me, “You have ALWAYS written because you are a fucking WRITER. And now, my friend, we are 40! It is time that you know in your heart you will ALWAYS write, because by now you have proved that you will. And it is also time that you deserve a job with goddamn benefits.”

When I told the yoga instructor in “Transcendent Practices” that I was depressed, she told me it was because there was a little girl inside me who wanted approval from her father (later, I learned this is what she said to every afab student who came to her with any concern whatsoever). I have no interest in whether there is a little girl inside me (although of course I am still looking for my father’s approval), but there remains the once-gifted student who is shocked to find themself a gay punk stoner working at McDonald’s. The gay punk stoner working at McDonald’s who went on to spend 15 years in commercial printing still struggles to believe that a clerical career, a “9 to 5” [7:30 to 4] in an office, is attainable. But because of the graduate service appointment I received, which allowed me to get my MFA without debt by working a student support position in an office, I was able to get a job that pays a living wage for the first time in my life. I turned in my HR paperwork yesterday – I’ll be working in Admissions and Registration at Spokane Community College.

I don’t know yet what my future writing practice will look like, because I don’t know yet what kind of energies my new job will draw on. But I’m looking forward to playing with routine and ritual, days of the week. I want my writing practice to become like reaching for soda cups while working the McDonald’s drive through or clicking functions in InDesign or the movement series I do every morning to prevent stiffness and osteoporosis. Muscle memory.

We got college credit in “knowing the knower.” I could not make that shit up.

Check that out, Mom and Dad: a 15+ year gap between undergrad and grad school!

Another insightful post! Glad to know you!

To be clear...I don’t mean my house is spotless or even “clean” by many standards! I’m talking more about making a space, putting a tablecloth and vase of flowers on my porch desk, throwing away scraps of paper on the inside desk, etc.